The turning point of World War II in Europe was the Allied triumph in a battle of minds. In effect, the Allies fought and won battles using armies that did not exist. The fictional British 4th Army froze 13 German divisions in place in Norway*, while the Germans held its 15th Army in reserve in the Pas de Calais region waiting for an attack by the equally fictitious First United States Army Group (FUSAG) Thanks to these two gallant but ghostly armies, the flesh-and-blood forces participating in the Allied invasion of Normandy on D-Day faced a diluted and relatively weak German army.

D-Day and the Normandy Invasion

The turning point of World War II in Europe was the Allied triumph in a battle of minds. In effect, the Allies fought and won battles using armies that did not exist. The fictional British 4th Army froze 13 German divisions in place in Norway*, while the Germans held its 15th Army in reserve in the Pas de Calais region waiting for an attack by the equally fictitious First United States Army Group (FUSAG) Thanks to these two gallant but ghostly armies, the flesh-and-blood forces participating in the Allied invasion of Normandy on D-Day faced a diluted and relatively weak German army.

The military historian Liddell Hart says that the purpose of strategy is “to diminish the possibility of resistance.” “Even if a decisive battle be the goal,” he says, “the aim of strategy must be to bring about this battle under the most advantageous circumstances. And the more advantageous the circumstances, the less, proportionately, will be the fighting.” To ensure a position of advantage on D-Day, Allied strategy called for keeping the German army too dispersed to mount an effective counterattack.

The super-ordinate objective of the Normandy invasion was clear. The Allies sought total victory in Europe, culminating in the defeat of Hitler’s last defenses in Berlin. The “beginning of the end,” as Winston Churchill called it, was the establishment of a beachhead, or lodgment, that would serve as a safe entry point into Europe by the Allied forces.

Because of the difficulty of landing an army on well-defended beaches, Allied planners had to identify or create elements of strategic advantage. If the German generals knew in advance exactly where to expect the invasion, they would gather all of their defenses in just the right spot to counter the allies. Thus, it was critical to spread the German defenses across the western coast of Europe so that few would be present at the eventual point of attack.

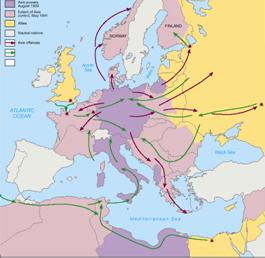

The Allies used a variety of misinformation techniques to convince Hitler that there were 350,000 Allied soldiers stationed in Scotland, ready to invade Europe through its northern regions. They invented a fictitious British 4th Army, code-named Skye, and touted it as the spearhead of the coming invasion of Norway and Scandinavia. By April of 1944, the radio and airwaves over Scotland were humming with communications about the bustling movement of brigades and equipment in preparation for an overseas assault. One easily “intercepted” message planted by the Allies contained an order for 1,800 pairs of crampons and as many snow ski bindings. [See this map of the German defenses across the Atlantic wall.]

The Germans monitored these communications and received confirmations from their own spies, who, in truth, were double agents working for the Allies. They also sent aerial reconnaissance over Scotland to get a look for themselves. German reconnoiters took pictures of hundreds of tanks and airplanes poised for the invasion. What their photographs did not reveal was that the planes were empty shells made of plywood and that the tanks were rubber “blow-up” models.

Meanwhile, the press in neutral Sweden carried (true) accounts of Allied engineers measuring the height of tunnels through which tanks and troop carriers might pass, as they conducted “preparations” for the coming invasion of Germany through northern Europe. The subterfuge, on its many fronts, worked. In the end, dozens of German divisions missed many critical battles in France while they waited in the north countries for the non-existent armies to arrive from the British Isles.

Thus the Allies won the battle of minds, through this and other even more important “ruse strategies.” Misleading the enemy is a stratagem dating back not centuries but millennia. As Sun Tzu wrote in The Art of War, “All war is based on deception.” To him, the greatest battle was the one not fought.

Spread and Focus Strategy

D-Day called for one of the most critical spread and focus strategies in history. The Allies needed an entry into Europe that would maximize their chances of success while minimizing the risk to lives and military assets. The map of Europe prior to D-Day illustrates how they arrived at their brilliant solution.

First, look at the extreme breadth of the Russian front. Keeping Germany occupied with a two-front war, which meant maintaining a coalition with Stalin and the Soviets, was a critical element of Allied strategy. As Americans, we remember the drama of D-Day, the liberation of Paris, and the Battle of the Bulge. But it was the “Barbarossa” campaign—a battle of unprecedented size between Russia and Germany—that made the invasion from the West possible. More than a million German soldiers were occupied on the eastern front on D-Day, when the Allies invaded the western front.

Second, take a glance at Scotland, facing Norway to the east. Norway was important to Hitler as the home of his U-boat bases. Taking advantage of the geographic proximity of Scotland to northern Europe, Allied leaders developed a strategy called Fortitude North. The Fortitude North ruse was intended to freeze in place the thirteen army divisions (over 130,000 soldiers, not to mention 90,000 navy and 60,000 Luftwaffe personnel) that Hitler had stationed in Norway, Denmark, and Finland. [note – I have seen estimates up to 27 divisions.] [1] To create a credible threat to the north, the Allies needed some loud saber-rattling in Scotland.

He who defends everything, defends nothing.

Frederick the Great

The Allies used a variety of misinformation techniques to convince Hitler that there were 350,000 Allied soldiers stationed in Scotland, ready to invade Europe through its northern regions. They invented a fictitious British 4th Army, code-named Skye, and touted it as the spearhead of the coming invasion of Norway and Scandinavia. By April of 1944, the radio and airwaves over Scotland were humming with communications about the bustling movement of brigades and equipment in preparation for an overseas assault. One easily “intercepted” message planted by the Allies contained an order for 1,800 pairs of crampons and as many snow ski bindings.

The Germans monitored these communications and received confirmations from their own spies, who, in truth, were double agents working for the Allies. They also sent aerial reconnaissance over Scotland to get a look for themselves. German reconnoiters took pictures of hundreds of tanks and airplanes poised for the invasion. What their photographs did not reveal was that the planes were empty shells made of plywood and that the tanks were rubber “blow-up” models.

Meanwhile, the press in neutral Sweden carried (true) accounts of Allied engineers measuring the height of tunnels through which tanks and troop carriers might pass, as they conducted “preparations” for the coming invasion of Germany through northern Europe. The subterfuge, on its many fronts, worked. In the end, dozens of German divisions missed many critical battles in France while they waited in the north countries for the non-existent armies to arrive from the British Isles. [For some thoughts about the Germans' misuse of strategic reserves, follow this link.]

Thus the Allies won the battle of minds, through this and other even more important “ruse strategies.” Misleading the enemy is a stratagem dating back not centuries but millennia. As Sun Tzu wrote in The Art of War, “All war is based on deception.” To him, the greatest battle was the one not fought.

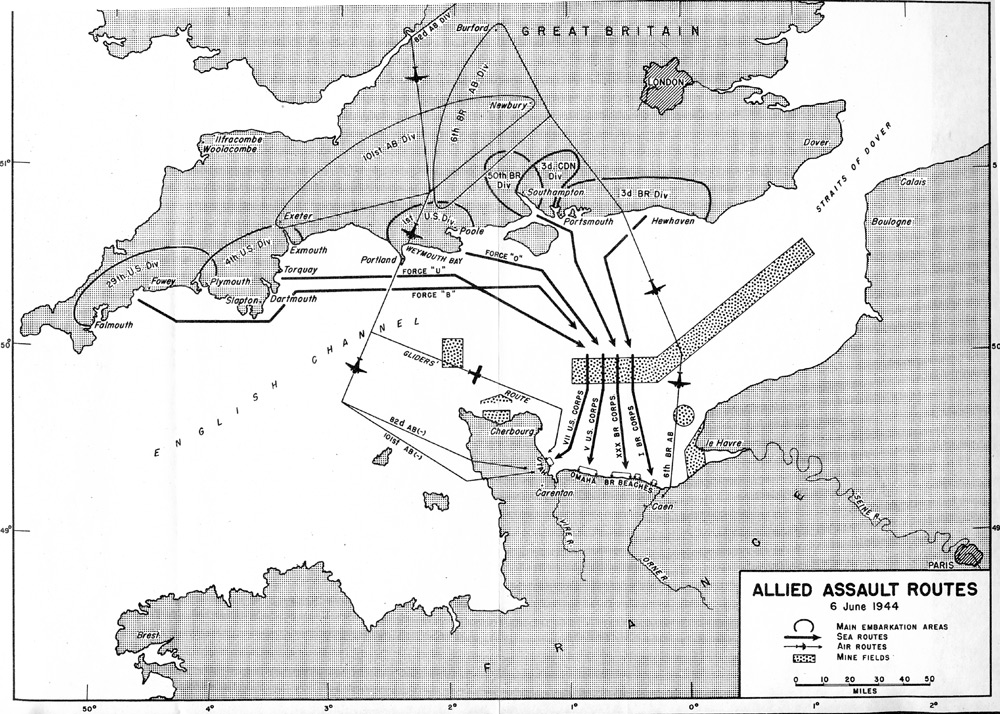

The Operational or Campaign Map View

To understand the narrower scope of the operational, as opposed to strategic, tier of decision-making, let us zoom in on a D-Day map of Southern Britain and French Normandy (figure X). Remember that in military parlance, a campaign is a series of related operations aimed at accomplishing an objective within a specific time and space. While the Normandy campaign was but one phase in the overall Allied strategy, it nonetheless required full-time work from tens of thousands of people in the weeks and months that preceded it.

In all cases, operational planning begins with a statement of strategy and objectives. In January of 1943, a year and a half prior to D-Day, the objective of the invasion was stated in this manner:

The object of Operation “Overlord” is to mount and carry out an operation, with forces and equipment established in the United Kingdom, and with target date the 1st of May, 1944, to secure lodgment on the Continent from which further offensive operations can be developed. The lodgment area must contain sufficient port facilities to maintain a force of some twenty six to thirty divisions, and enable that force to be augmented by follow-up shipments from the United States or elsewhere of additional divisions and supporting units at a rate of three to five divisions per month.

This statement of purpose clarified an exact and narrow objective and allowed planning to proceed.

Once purpose is stated, it is always important to articulate a set of operating principles that will further guide decision-making. Plans for the Normandy campaign were partly based on a set of principles developed under the leadership of Brigadier General John W. O’Daniel and published in May of 1943, a little over a year before D-Day. Just as many business leaders glean useful ideas from the words of Sun Tzu, Clausewitz, and Napoleon, so might we draw on O’Daniel and his team for insight into operational planning. The following are extracted from the list:

- Army, Navy and Air personnel definitely should be unified under one command, for planning, training and operation. In furtherance of this principle, one headquarters under which there is only one joint staff should be established.

- Any contemplated invasion should be predicated upon accurate and evaluated … information.

- All ships and landing craft should be so loaded that the loss of one or more vessels will not deprive the landing force of any one type of essential troops, weapons, vehicles or supplies.

- Any component of an assault force, no matter how small, should never be separated from its essential combat equipment.

- It is essential that personnel participating in assault carry only the barest essentials necessary for combat, in food and clothing.

- When the assault forces have reached their objectives other troops should be immediately available to exploit the initial success.

- Invasions should be made in darkness. A complete RLT [Regimental Landing Team] should be on the beach before daylight.

- The RLT Commander should make the majority of decisions as to the loading and unloading of the ships assigned to his landing team.

Some of these principles were violated on D-Day itself, to the detriment of the landing forces. But, clearly, principles like these, calling for clarity of leadership, flexibility of personnel, actionable intelligence, tactical decision-making at the point of attack, and contingency planning are useful in any operational planning effort.

The next step in operational planning is an assessment of the strategic situation. In the case of war, intelligence gathering would include assessment of “enemy strength, locations and abilities; the types, quantities, and quality of troops and equipment available; and the terrain on which the battles would be fought.”[1] In the beginning, Normandy campaign planners had more information on the enemy’s resources than on their own.

Next, a number of decisions are to be made. For the Normandy campaign these included the exact landing sites; the order in which men and equipment would arrive; the time and date of invasion; the extent of preliminary bombardment needed to weaken German defenses without providing the enemy undue warning.

“…you’re going to find confusion.”

General Norman Cota preparing his men for D-Day

In a sense, operational planning is the bridge from strategic intent to what actually happens. Despite the incredible amount of planning prior to D-Day, the operation itself ended up vastly different than conceived. Stormy weather, failed technology, and human error led to many unforeseen circumstances. On June 5, known as D minus One, General Norman Cota, a particularly strong operational leader, warned his troops to expect the unexpected:

“This is different from any of the exercises you’ve had so far. The little discrepancies that we tried to correct on Slapton Sands [the site of a practice operation on England’s southern coast] are going to be magnified and are going to give way to incidents that you might at first view as chaotic. The air and naval bombardment and the artillery support are reassuring. But you’re going to find confusion. The landing craft aren’t going in on schedule and people are going to be landed in the wrong place. Some won’t be landed at all. The enemy will try, and will have some success, in preventing our gaining lodgment. But we must improvise, carry on, and not lose our heads.”

General Cota’s words, as we know, were prescient. No operational plan should come without this kind of warning. It is unrealistic to expect that any plan at the operational or campaign level can outline what to do under all contingencies. People must be aware that there will be confusion and foggy circumstances ahead. Communication like Cota’s provides the best transition to the realm of tactical, on-the-ground decision-making.

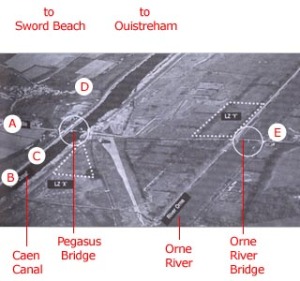

The Tactical Map View

Finally, we pan in on the map once more to view an area of just a few acres to the east of the invasion site. As noted, Allied strategy succeeded in dispersing German forces just prior to D-Day. Still, once alarmed, the Germans were sure to mount a counterattack from the east as quickly as possible. Allied operational planning called for sealing off the eastern flank of the invasion area, defined by the Orne River and the Caen Canal. Two critical bridges stood between the German reinforcements and the Normandy beaches where thousands of vulnerable soldiers were landing. These bridges came to be known as the Pegasus and Horsa bridges.

In two tactical skirmishes that lasted only hours during the night before to the Allied landing, two gliders carrying X men landed near the bridges, and after a short firefight, American platoons ousted the German guards and took control of this essential pinch point. [ In other words, everything went according to plan.

A third planned skirmish involved the destruction of a battery of artillery the Germans had moved from the French Maginot Line to ground outside the Normandy town of Merville. A force of 750 airborne troops was assigned to attack and destroy these “guns of Merville” during the night before D-Day. A British officer named T.B.H. Otway was assigned to lead the effort.

In contrast to the attacks on the Pegasus and Horsa bridges, there was little in common between the operational planning for the Merville maneuvers and their actual execution. Rather, everything went wrong for Otway and his troops. Pilots panicked in the face of anti-aircraft flak and dropped many paratroopers too far from the target area to participate in the operation. Critical equipment, including mortars, mine detectors, radios, and weapons, were not recovered after being dropped from the air. More important, a planned air attack to drop bombs in order to create foxholes to protect the assaulting soldiers failed when all the bombs missed their target. But Otway displayed good judgment under fire and improvised solutions. The men on the ground adjusted to unanticipated and quickly changing circumstances, deviating significantly from the operational plan. In the end, through heroic and brave efforts, Otway and his men drove the Germans out of the area and rendered the guns of Merville useless. They succeeded because of excellent tactical decision-making.

* Notes on Military Size of force

US, British, Canadian infantry division in WW2 – 15,000 to 20,000 strong on D-Day

Airborne divisions half that size

German division less than 10,000

Squad – 9 to 12

Platoon – 3 or 4 squads – about 40

3-4 platoons to a company – about 125

3-4 companies to a battalion – about 500

3-4 battalions to a regiment – about 2,000

Division includes all the non-combat people

***

Here is a strategic map of Europe on D-Day